Category Archives: Scriptural Authority

Losing Paul: What Happens If We Deny The Apostle’s Authority?

Posted by Joseph Torres

What would happen if we removed Paul and his influence from the New Testament? That’s a question I’ve been thinking about ever since I was asked to help respond to a person who denied Paul’s apostolic authority. The more I reflected on what would be lost if Paul were removed, the more it appears that the loss of Paul from the canon creates an unstoppable domino effect.

So, how should we respond to a person who seemingly wants to affirm Scripture, but denies Paul’s apostolic authority?

First Things First. The important thing to remember is that your view is not on trial. You hold to the historical and consistent witness of Christians for 2,000 years in affirming Paul’s apostolic authority. The burden of proof is on the person who denies this uniformly affirmed Christian position. Questions should be asked. On what ground does he deny Paul’s authority? It cannot be on the authority of the Bible. Second Corinthians was written defending that very thing! Those who have called Paul’s apostolic authority into question throughout church history have usually been heretics.

The Price of Paul. According to the New Testament, Peter affirms Paul’s apostolic authority when he acknowledged that like the Prophets Moses and Isaiah, Paul’s writing is inspired by the Holy Spirit. Peter writes:

And count the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as our beloved brother Paul also wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, as he does in all his letters when he speaks in them of these matters. There are some things in them that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures. (2 Peter 3:15-16)

And of course, there is the repeated testimony to Paul’s calling and conversation in Acts written by Luke (see Acts 9, 22, and 26). Likewise, half the book of Acts is dedicated to demonstrating that Paul was faithful to Christ’s calling on his life.

Rejecting Paul’s apostolic authority also has seriously damaging consequences for how we understand all of the New Testament. Here how that line of thinking goes: If Paul has no God-given apostolic authority, then he was not truly called by Jesus himself on the Road to Damascus. If Paul was not truly called by Jesus himself on the Road to Damascus, then the author of Acts (Luke) made up those accounts and therefore cannot be trusted. If Luke cannot be trusted, then the Gospel by his name cannot be trusted. If we lose Luke’s Gospel, we lose ¼ of the historical testimony to earthly life of Christ, as well as many details about the facts of Jesus birth.

A shockwave runs through the New Testament simply by calling into Paul’s authority into question. All distinctive teachings of Paul (teaching that are unique to Paul’s writings and not found in other Gospels or epistles) are lost.

But there’s more…

As we noted above, Peter endorsed Paul. This would mean that Peter was either mistaken or deceived, calling his authority into question. But we must remember that Peter is regularly acknowledged as the source behind Mark’s Gospel, which is usually recognized as the original Gospel and the Gospel which the apostle Matthew expanded upon. This means if Paul loses all credibility…

- Luke loses all credibility

- Peter loses all credibility

- Mark loses all credibility

- Matthew loses all credibility.

With further, and more detailed, argumentation I believe I could push this further, but in this conservative estimate the loss of Paul would reduce our New Testament from 27 books to a mere 8 (John, Hebrews, James, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd John, Jude, and Revelation).

That’s a lot to sacrifice.

Posted in Apostle Paul, Scriptural Authority

On Inerrancy and the Biblical Use of Secondary Sources

Posted by Joseph Torres

In writing their inspired messages, several biblical authors saw fit to mention or cite books that would lend support to their historical claims. In the book of Ezra, over one-third of its contents are actually quotes from official legal documents. The question is raised, “if uninspired material is quoted in a supposedly infallible book, how does this effect the biblical understanding of inerrancy?”

In writing their inspired messages, several biblical authors saw fit to mention or cite books that would lend support to their historical claims. In the book of Ezra, over one-third of its contents are actually quotes from official legal documents. The question is raised, “if uninspired material is quoted in a supposedly infallible book, how does this effect the biblical understanding of inerrancy?”

On the surface it would seem that quoting flawed, or at least fallible, sources would cast a shadow of doubt on the truth of the Bible. Let’s explore what these citations or references do not imply. First, in quoting these sources the biblical writers and/or editors did not imply that books like The Prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite, and The Annotations on the Books of the Kings were separate vehicles of inspired revelation. When Jude makes reference to the Book of Enoch and The Bodily Assumption of Moses he is not telling us that we should find these books and include them into the canon of Scripture. Acknowledging that uninspired books that contain truth do in fact exist does not imply that we lack a complete canon and should therefore seek out these ‘revelations.’

Second, when we see a note directing our attention to a Book of Records of Nathan the Prophet it does not necessarily mean the inspired Writers agreed with everything in that uninspired source. The Book of Enoch contains several things that a biblically informed Christian would reject. But, as noted earlier, this does not stop an author from accepting a particular truth in a document. Paul, in Acts 17, made reference to the Greek philosopher Epimenides when he acknowledged that in God we “live and move, and have our being”, and that “we are His offspring”. Yet as we examine the actual work he cited, Epimenides was not referring to YHWH, the God of Israel, but of Zeus, the supreme deity of the Greek pantheon. Does this mean that Paul condoned pagan idol worship? No, of course not. Paul was simply confirming to the men of Athens that in our supreme Creator we owe all of our existence, though they substituted this Creator with Zeus.

Lastly, and typing together our first two points, when quoting outside sources the Prophets and Apostles claimed neither that those books where an authoritative rule of faith, nor were they infallible. Historical documents were cited simply to corroborate the truthfulness of what an inspired writer claimed. All these references were perfect, infallible uses of imperfect, fallible documents.

Yet, with these few notes having been made, we must now look to what actually was implied by the biblical Writers when they quoted from uninspired documents. First, if we are to define inerrancy by saying that the Bible is correct in all that it affirms, we must confess that these quotations taken from other sources are indeed correct, and reliable in conveying the reality which they dealt with. The entire concept of biblical inerrancy, when properly understood, is the natural, logical conclusion to the doctrine of biblical inspiration. The reasoning goes as follows:

- God is truth, and cannot tell any falsehood. (John 3:33, 17:3, 1 Jn. 5:20)

- All Scripture is inspired by God[1], and is the very source in which we find God speaking to us. (2 Tim. 3:16-17)

- Therefore, all Scripture is without error in everything it affirms, and correct in all it documents. (Ps.19:7, Isa. 65:16)

It is with this presupposition that we come to the texts in question.

Another point we must realize is that the writers of these particular texts knew that the resources they cited would hold quite a bit of weight with their readers. For example, when Ezra quotes at length from the letters of King Darius and King Artaxerxes he knew that the authority lent to his writing by official royal decrees would confirm his writings. Therefore, anyone contesting the authenticity of his writing could confirm them within the annals of royal decrees.

And lastly, it is worthy of mention that we must always keep in mind that the concept of biblical inerrancy does not imply that the canon was written in a vacuum. When authors such as Ezra or the writers of such books as 1 & 2 Kings and Chronicles were addressing the pressing issues of their day, they were not exempt from gathering source data much like we today do.

The chief difference between their research and our own is that God superintended their writings of biblical authors in such a way, through inspiration, that their citations and references were completely free from error and misguidance.

[1] The literal rendering of the Greek text is “God-breathed”, theopneustos. For more see my What is Biblical Inerrancy? A Six-Part Series

The Clarity, Necessity, and Sufficiency of Scripture

Posted by Joseph Torres

John Frame on three essential characteristics of Scripture:

John Frame on three essential characteristics of Scripture:

Now I want briefly to mention [several] important things about the Bible. The first is its clarity [See Westminster Confession of Faith 1.7.].

Clarity. At the time of the Reformation, some Roman Catholics were saying that lay people should not read the Bible, since only people in the church hierarchy could properly understand it. The Reformers did not say that everything in the Bible is perfectly clear. But they did say that the basic message of salvation is sufficiently clear that anyone can understand it, either by reading it himself, or by using ordinary means of grace, such as talking to a pastor. By the way, the power of the word, its authority, and its clarity, form a triad that corresponds to the Lordship attributes. For in Deut. 30:11-14 and Rom. 10:6-8 the clarity of the word is based on the nearness of God to his people, the presence of God among his people.

Necessity. Necessity simply means that without God’s Word we have no relationship with him. Without his commands he is not our Lord, for the Lord is by definition one who gives authoritative commands to his people. And without his word, we have no authoritative promises either, so he cannot be our savior.

Sufficiency. Sufficiency means simply that in Scripture we have all the words of God we need [See Westminster Confession of Faith 1.6.]. We should not try to add to them, and we dare not subtract from them, since we live by every word that comes from God.

Scripture itself tells us not to add or subtract (Deut. 4:2, 12:32, Rev. 22:18-19). And it tells us clearly not to add human tradition to the word: that is, don’t put human tradition on the same level as God’s word, as the Pharisees did (Deut. 18:15-22, Isa. 29:13, Matt. 15:1-9, Gal. 1:8-9, 2 Thess. 2:2). Human tradition is not a bad thing. But it is not God’s word. When we try to put it on the same level as God’s word, we are saying that God’s word is not enough, that it is insufficient.

This is true of all Scripture, both Old and New Testament. But there is also a special sense in which the New Testament gospel is sufficient. Just as Jesus’ death and resurrection are sufficient to save us, so the apostles’ message about Jesus is sufficient to give us all the blessings of Jesus’ salvation (2 Pet. 1:2-11, Hen. 1:1-3, 2:1-4). So we should not expect God to give us further revelation of the same authority as the Bible.

People sometimes say that Scripture is sufficient for theology, but not for other areas of life, like science, history, plumbing, politics, car repairs. But that idea misunderstands the sufficiency of Scripture. Remember always: Scripture is sufficient as the word of God. It gives us all the words of God we will ever need. So Scripture contains all the word of God we need for theology—but also for ethics, politics, the arts, plumbing and car repair.

Certainly for all these disciplines we need knowledge from outside Scripture too. That’s even true of theology. Theologians need, for example, to know the rules of Hebrew Grammar; but Scripture doesn’t give these to us. They need to know the history of the ancient world; but Scripture only gives us part of that history. So in order to use the Bible, we need to know things outside the Bible.

That’s also true in ethics. For example, the Bible doesn’t mention abortion. We have to learn what abortion is from extra-biblical sources. But Scripture does say some things about murder, and about unborn human life. When we bring the biblical principles together with our extra-biblical knowledge of what abortion is, it becomes pretty obvious that “thou shalt not murder” implies “thou shalt not abort.”

The basic point to be remembered here is that no kind of knowledge from outside the Bible is worthy to be added to Scripture. That includes the traditions of the Roman church, claims of contemporary prophets… and even the confessions and traditions of the Protestant denominations.

-John M. Frame, Salvation Belongs to the Lord

God’s Word of Power

Posted by Joseph Torres

John Frame makes the following subpoints about the word of God in his larger discussion on the subject in Salvation Belongs to the Lord:

John Frame makes the following subpoints about the word of God in his larger discussion on the subject in Salvation Belongs to the Lord:

Let me make several subpoints, beginning from the more obvious, moving to the less obvious:

- The word reveals God. Obviously, when God speaks, he reveals his mind, his will, his heart. According to Deut. 4:5-8, the nations around Israel learn what kind of God Israel has when they hear his word. The righteousness of God’s statutes and rules reveals the righteousness of God himself, and indeed his nearness to Israel, verse 7.

- Word and Spirit work together. We saw in 1 Thess. 1:5, that the word comes to us in power and in the Spirit. When the word works in power, the Spirit is right there working with it. That means that when the word is among us, God also is among us.

- God performs all his actions by speaking. There are several classes of divine actions mentioned in the Bible. These include God’s eternal plan, creation, providence (including miracle), and his judgments and blessings on creatures. These actions line up parallel to the lordship attributes. The eternal plan shows his lordship attribute of authority, creation and providence his control, and his judgment and blessing his presence. But my point here is that every one of these acts God performs by speaking, by his word. His eternal counsel is a form of speech (Ps. 33:11, Acts 2:23, 4:28), as is creation (Gen. 1:3, Ps. 33:6, John 1:3), providence (Ps. 148:8), judgment (Gen. 3:17-19, Matt. 25:41-43, John 12:47-48) and grace (Matt. 25:34-36, Rom. 1:16). So, again, you never find God without his word.

- God is distinguished from other gods by the fact that he speaks. The word is so important that it is the means by which Scripture distinguishes between him and idols. The idols are “dumb.” God, however, is by his nature word. See this contrast in Hab. 2:18-20, 1 Kings 18:24, 26, 29, Ps. 115:4-8, 135:15-18, 1 Cor. 12:2. As speech distinguishes God from pretenders to deity, it thereby characterizes his nature at a deep level.

- The persons of the Trinity are distinguished by their role in the divine speech. We usually define the Trinity in terms of a family: the Father and the Son; but when we do that it is hard to bring the Spirit into that particular metaphor. But Scripture also speaks of the Trinity using a linguistic metaphor: the Father is the speaker (Ps. 110:1, 147:4, Isa. 40:26), the Son the word (John 1:1-14, Rev. 19:13), and the Spirit is the breath that carries the word to its destination (Ps. 33:6, 2 Tim. 2:16). The words for “Spirit” in Greek and Hebrew mean “breath” or “wind.” When I speak to you, my breath pushes my words out of my mouth and begins an air current that goes to your eardrums. In the same way, in God, the Father speaks the Word, and the Spirit carries that Word so that it accomplishes its purpose, as we saw in 1 Thess. 1:5. So the word is so important to God’s nature that it can be used to define the Trinity.

- The speech of God has divine attributes: it is righteous (Ps. 119:7), faithful (Ps. 119:86), wonderful (Ps. 119:129), holy (2 Tim. 3:15), eternal (Ps. 119:89, 160), omnipotent (Gen. 18:14 [This verse reads literally, “No word of God is void of power.”] Isa. 55:11), perfect (Ps. 19:7). Only God has these attributes in total perfection. So the word is God.

- The word of God is an object of worship. In Psm. 56:4, David says, “In God, whose word I praise, in God I trust; I shall not be afraid. What can flesh do to me?” He repeats this praise for the word in verse 10 (cf. Ps. 119:120, 161-62, Isa. 66:5). This is remarkable, for only God is the object of religious praise. To worship something other than God is idolatrous. Since David worships the word here, we cannot escape the conclusion that the word is divine.

- The word is God, John 1:1, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” We usually use this passage to show the deity of Christ, and it is an excellent passage for this purpose, as we shall see in Chapter 10. But now I want you to see that this passage does not only identify Jesus with God. It also identifies God’s speech with God. The phrase “in the beginning” takes us back to Genesis 1. In that passage, the word was the creative word of God, the word that made the world. John 1:3 emphasizes the creative work of the word, “All things were made through him [that is, through the word], and without him was not any thing made that was made.” So the word that “was God” in verse 1 was, not only Jesus, as verse 14 clearly indicates (“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us”), but also the speech of God commanding the light to come out of darkness in Gen. 1:3. Cf. 2 Cor. 1:20, Heb. 1:1-3, 1 John 1:1-3, Rev. 3:14, 19:13.

So the word is God, and God is the word. Where God is, the word is, and vice versa. God’s word is not only powerful and authoritative, it is the very presence of God in our midst. How can we understand this? We can think of God’s word, as John did in the first chapter of his gospel, as somehow identical with Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity. So when God speaks to us, Jesus is there.

-John M. Frame, Salvation Belongs to the Lord

The Gift of God’s Written Word

Posted by Joseph Torres

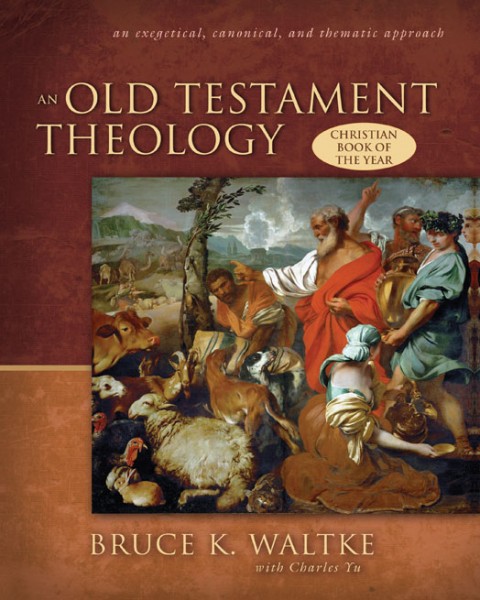

Bruce Waltke on the gift of God’s word:

Bruce Waltke on the gift of God’s word:

[Scripture] is God’s word to the church…not merely a historical artifact of Israel’s religion. In the Bible’s pages, the church learns what to proclaim and how to live as a kingdom of priests, a holy people, and a light to the nations–to act justly, love mercy, and walk circumspectly. The church learns how to worship, pray, adore God, and confess sin.

The theologian should consider the Bible’s Source as inerrant and its teaching as infallible; should study the text for meaning rather than just as an account of the events recorded therein; should read the Old Testament as a unity, a product of the one Author; should read reverently, recognizing the authority of the text for the present day.”

Bruce K. Waltke, An Old Testament Theology

God’s Personal Words

Posted by Joseph Torres

This pretty much sums up the thesis of Frame’s Doctrine of the Word of God:

This pretty much sums up the thesis of Frame’s Doctrine of the Word of God:

God’s speech to man is real speech. It is very much like one person speaking to another. God speaks so that we can understand him and respond appropriately. Appropriate responses are of many kinds: belief, obedience, affection, repentance, laughter, pain, sadness and so on. God’s speech is often propositional: God’s conveying information to us. But it is far more than that. It includes all the features, functions, beauty, and richness of language that we see in human communication, and more. …My thesis is that God’s word, in all its qualities and aspects, is a personal communication from him to us.

-John M. Frame, Doctrine of the Word of God

Do Christians Worship a Book?

Posted by Joseph Torres

John Frame reflects on the objection that evangelicals worship the Bible, also known as ‘bibliolatry’:

John Frame reflects on the objection that evangelicals worship the Bible, also known as ‘bibliolatry’:

The psalmists view the words of God with religious reference and awe, attitudes appropriate only to an encounter with God himself. The psalmist trembles with godly fear (Ps. 119:120; cf. Isa. 66:5), stands in awe of God’s words (Ps. 119:161), and rejoices in them (v. 162). He lifts his hands to God’s commandments (v. 48). He exalts and praises not only God himself, but also his “name” (Ps. 9:2; 34:3; 68:4). He gives thanks to God’s name (Ps. 138:2). He praises God’s word in Psalm 56:4,10. This is extraordinary, since Scripture uniformly considers it idolatrous to worship anything other than God. But to praise or fear God’s word is not idolatrous. To praise God’s word is to praise God himself.

Does this worship justify bibliolatry? The Bible, as we will see later, is God’s word in a finite medium. It may be paper and ink, or parchment, or audiotape or a CD-ROM. The medium is not divine, but creaturely. We should not worship the created medium; that would be idolatry. But through the created medium, we received the authentic word of God, and that word of God should be treated as if God were speaking it with his own lips. It should be received with absolute trust, obedience, and, yes, worship.

Opponents of evangelicalism commonly say that it is idolatrous to accept any human word as having divine authority. Scripture, however, teaches that we should accept the divine-human words on its pages precisely as God’s own. Evangelicals are often too sensitive to the charge of bibliolatry. That charge is illegitimate, and it should not motivate evangelicals to water down their view of Scripture.

-John M. Frame, Doctrine of the Word of God, 67-68

Inerrancy and Problem Passages

Posted by Joseph Torres

John Frame, in Doctrine of the Word of God, explains how one should maintain a belief in the inerrancy of Scripture in light of the difficulty of ‘problem passages’:

John Frame, in Doctrine of the Word of God, explains how one should maintain a belief in the inerrancy of Scripture in light of the difficulty of ‘problem passages’:

Now, when many readers look at Scripture, it appears to them to contain errors. So many writers have urged that we should not derive our doctrine of Scripture merely from its teachings about itself, but that we should take into account the phenomena. And if we take the phenomena seriously, they tell us, we will not be able to conclude that Scripture is inerrant. This approach is sometimes called and inductive approach…

I believe the inductive method, so describe, is a faulty method for determining this character of Scripture. Of course, Scripture contains “difficulties,” problems, apparent errors. But what role should these play in our formulation of the doctrine of Scripture? It is important to remember that all doctrines of the Christian faith are beset by problems. The doctrine of God’s sovereignty seems in the view of many readers to conflict with the responsibility of human beings, and the apparent contradiction has led to many theological battles. The doctrine of the Trinity says that God is both three and one, and the relation between his threeness and his oneness is not easy to put into words. When speaking of Christ, we face the problem that he is both God and man, both eternal and temporal, both of omniscient and limited in his knowledge. Would anyone argue that because of these problems we should not confess that God is sovereign, that man is responsible, that God is three and one, that Jesus is divine and human?

Does the Doctrine of Biblical Inspiration Suppress the Importance of Scripture’s Human Authors?

Posted by Joseph Torres

Here is the single greatest explanation of the divine-human partnership in the creation of Holy Scripture I’ve ever read. Here Scott Swain, in Trinity, Revelation, and Reading, clears away misunderstandings of biblical inspiration. The book is a tad bit pricey, but analyses as good as this make it worth every penny. I quote at length:

Here is the single greatest explanation of the divine-human partnership in the creation of Holy Scripture I’ve ever read. Here Scott Swain, in Trinity, Revelation, and Reading, clears away misunderstandings of biblical inspiration. The book is a tad bit pricey, but analyses as good as this make it worth every penny. I quote at length:

*********************************************************************************

Some worry that such an emphasis on the Spirit’s power in the production of Holy Scripture overrides or ignores it’s human authorship. The more the Spirit’s responsibility for this book is stressed, the more the intelligence, freedom, and personal activity of the Bibles human authors are suppressed – or so it is argued.

But this worry is unfounded, because the One who is “the Spirit of the Father and the Son” is also “the Lord and Giver of Life” (the Nicene Creed). The presence and operation of the Spirit’s sovereign lordship in the production of Holy Scripture does not lead to the suppression or overruling of God’s human emissaries in their exercise of authorial rationality and freedom. Rather, his sovereign lordship leads to their enlightening and sanctified enablement. The Spirit who created the human mind and personality does not destroy the human mind and personality when he summons them to his service. Far from it. The Spirit sets that mind and personality free from its blindness and slavery to sin so that it may become a truly free, thoughtful, and self-conscious witness to all that God is for us in Christ. He bears his lively witness and therefore prophets and apostles also bear their lively witness (Jn. 15.26-27). The Spirit creates a divine-and-human fellowship – a common possession and partnership – in communicating the truth of the gospel (Jn. 16.13-15).

Four Favorites on the Doctrine of Scripture

Posted by Joseph Torres

From the article Four Favorites on the Doctrine of Scripture

by John Frame

1. B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible

These essays are the most influential in forming the evangelical and Reformed view of Scripture in the twentieth century. They are around 100 years old, but the exegetical arguments still hold up. The book is a formidable work of godly scholarship. It is the starting point for most current discussions of biblical authority and inerrancy. Warfield’s view was not original, though some have claimed that it was. His was the traditional position of orthodox Christianity. But he was creative in his powerful defense of that position.

2. Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, volume 1 (of 4)

Bavinck’s theology is the most important work of Reformed systematic theology in the past century. The section on Scripture is marvelously comprehensive and nuanced. In my judgment, there is no difference between his position and that of Warfield, but his vocabulary and emphasis are different. He and Warfield give us “two witnesses,” coming from different cultures, testifying to the truth of Scripture as God’s word.

3. Meredith G. Kline, The Structure of Biblical Authority (Eerdmans, 1972).

This is the most important breakthrough in the doctrine of Scripture since Warfield. Shows that Scripture has the character of a written treaty, of which God is the author, and to which believers must be committed without reservation. I have disagreed with Kline on some other matters, but I believe this book contains a powerful argument. Kline shows that the idea of a written, authoritative word of God is essential to God’s plan of redemption.

4. Ned Stonehouse and Paul Woolley, eds., The Infallible Word (P&R, 2003).

These are cogent articles by the old (around 1946) Westminster Seminary faculty, dealing with various aspects of biblical authority. I keep coming back especially to John Murray’s “The Attestation of Scripture” and Cornelius Van Til’s “Nature and Scripture.” Murray gives a concise, definitive exposition of Scripture’s self-witness. Van Til shows that both general and special revelation are necessary, authoritative, clear, and sufficient for their respective purposes, and that they stand opposed to the worldviews of non-Christian philosophies.

Scripture is Eternally Youthful

Posted by Joseph Torres

Another excerpt from Trinity, Revelation, and Reading:

Another excerpt from Trinity, Revelation, and Reading:

The writing of the Law thus provided an enduring means whereby God’s covenantal word through his authorized agents could reach endless generations of his people. And this is exactly how later generations of God’s people received his written word, not simply as a record of past acts of revelation, but as the divinely authorized literary means whereby the living God continually speaks to his people (see esp. Heb. 3.7ff; also Rom. 15.4). What Bavinck says of Holy Scripture in general applies to the Old Testament in particular. It “is not in arid story or ancient chronicle but the ever-living, eternally youthful word of God, which God, now and always issues to his people. It is the eternally ongoing speech of God to us.” The scriptures are the viva vox Dei, the living voice of God.

-Scott. R. Swain, Trinity, Revelation, and Reading,

Posted in Scott R. Swain, Scriptural Authority

Tags: Bible, Herman Bavinck, Scott Swain, Scripture, word of God

God Breathed Scripture

Posted by Joseph Torres

In Trinity, Revelation, and Reading, Swain has some wonderful things to say about the nature of biblical inspiration and its dual authorship. Here’s another sampling of his work:

In Trinity, Revelation, and Reading, Swain has some wonderful things to say about the nature of biblical inspiration and its dual authorship. Here’s another sampling of his work:

“To say that Scripture is “God breathed” is therefore to say that, in the writings of these divinely appointed prophets and apostles, and by virtue of the Spirit’s power to awaken spiritual understanding and utterance, we have God’s own covenantal and Christological word. J.I. Packer’s Trinitarian definition of biblical inspiration is apropos: Scripture in its entirety is “God the Father preaching God the Son in the power of God the Holy Spirit.” “All Scripture is God breathed” (2 Tim. 3.16), the almighty utterance of the triune king”

– Scott R. Swain, Trinity, Revelation, and Reading: A Theological Introduction to the Bible and its Interpretation, 65

Posted in Scott R. Swain, Scriptural Authority

Kruger on Canon

Posted by Joseph Torres

Dr. Michael J. Kruger, Professor of New Testamentand Academic Dean at Reformed Theological Seminary, Charlotte is the author of Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books. In March (2012) he delivered the Kistemaker Lecture Seriesat RTS-Orlando on the Canon of Scripture. Here are the lectures:

Dr. Michael J. Kruger, Professor of New Testamentand Academic Dean at Reformed Theological Seminary, Charlotte is the author of Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books. In March (2012) he delivered the Kistemaker Lecture Seriesat RTS-Orlando on the Canon of Scripture. Here are the lectures:

- “The Definition of ‘Canon’: Exclusive or Multi-Dimensional?“

- “The Origins of Canon: Was the Idea of a New Testament a Late Ecclesiastical Development?“

- “The Artifacts of Canon: Manuscripts as a Window into the Development of the New Testament“

- “The Messiness of the Canon: Do Disagreements Amongst Early Christians Pose a Threat to Our Belief in the New Testament?“

The reviews of Canon Revisited mark it out as a major work on the subject.

“Of all the recent books and articles on the canon of Scripture, this is the one I recommend most. It deals with the critical literature thoroughly and effectively while presenting a cogent alternative grounded in the teaching of Scripture itself. Michael Kruger develops the historic Reformed model of Scripture as self-authenticating and integrates it with a balanced appreciation for the history of the canon and the role of the community in recognizing it. This is the definitive work on the subject for our time.”

—John M. Frame, J. D. Trimble Chair of Systematic Theology and Philosophy, Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando, Florida

“Michael Kruger has written the book on the canon of Scripture that has been much needed for a long time. His focus is not on the process, but on the vitally important question of how Christians can know that they have the right books in their canon of Scripture. The question is an excellent one and needs to be addressed honestly and competently. Kruger does just that. This excellent book goes a long way toward clearing up confusion and misguided theories. I highly recommend it.”

—Craig A. Evans, Payzant Distinguished Professor of New Testament, Acadia Divinity College and Acadia University

“Here, finally, is what so many pastors, seminary professors, and students have long been waiting for: a clear, well-informed, and scripturally faithful answer to the question of how Christians should account for the New Testament canon. Perhaps not since Ridderbos’s Redemptive History and the New Testament Scriptures has there appeared such a valuable single source on the New Testament canon that is both historically responsible and theologically satisfying (and this book improves on Ridderbos in many ways). Michael Kruger’s work will help readers get a handle on what may seem like a myriad of current approaches to canon, whether ecclesiastical or critical. This book will foster clearer thinking on the subject of the New Testament canon and will be a much referenced guide for a long time to come.”

—Charles E. Hill, Professor of New Testament, Reformed Theological Seminary

Scripture as Law

Posted by Joseph Torres

“Everything in Scripture has the force of law. What it teaches we are to believe; what it commands, we are to do. We should take its wisdom to heart, imitate its heroes, laugh at its jokes, trust its promises, and sing its songs.” – John Frame

Posted in John Frame, Scriptural Authority

What is Organic Inspiration?

Posted by Joseph Torres

Christians uniformly confess that the Bible is inspired. Paul, in 2 Tim 3:15-17, says that all Scripture is “God-breathed” and thus the very word of Yahweh, the Creator and Lord of the universe. But, Christians also confess that “men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Pet. 1:21). In a way that quite parallel (though not identical) with the doctrine of Christ’s 2 natures, the Bible is both the verbal communication of God, and the fully verbal communication of it’s human authors. And we need to maintain this balance of dual-authorship or we’ll go off the deep end. Admittedly, for most Christians we run the risk of denying (in theory or practice) that God really did use human authors.

Christians uniformly confess that the Bible is inspired. Paul, in 2 Tim 3:15-17, says that all Scripture is “God-breathed” and thus the very word of Yahweh, the Creator and Lord of the universe. But, Christians also confess that “men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Pet. 1:21). In a way that quite parallel (though not identical) with the doctrine of Christ’s 2 natures, the Bible is both the verbal communication of God, and the fully verbal communication of it’s human authors. And we need to maintain this balance of dual-authorship or we’ll go off the deep end. Admittedly, for most Christians we run the risk of denying (in theory or practice) that God really did use human authors.

I would suggest that the best way of thinking about the dual-authorship of Scripture is what come to be known as “organic” inspiration. Now I’ll turn it over to 3 “Dutch masters” to clarify this position. First Louis Berkhof:

The proper conception of inspiration holds

that the Holy Spirit acted on the writers of the Bible in an organic way, in harmony with the laws of their own inner being, using them just as they were, with their character and temperament, their gifts and talents, their education and culture, their vocabulary and style. The Holy Spirit illumined their minds, aided their memory, prompted them to write, repressed the influence of sin on their writings, and guided them in the expression of their thoughts even to the choice of their words. In no small measure He left free scope to their own activity. They could give the results of their own investigations, write of their own experiences, and put the imprint of their own style and language on their books. -Louis Berkhof, Summary of Christian Doctrine, chapter 3

This explains a lot, doesn’t it? John writes quite differently than Paul. And even Paul writes differently from letter to letter. Colossians and Ephesians are quite similar, but Philippians and Galatians are quite different. In the former, Paul is happy and rejoicing, in the latter Paul is upset and agitated. Herman Bavinck takes us a bit further, clarifying what organic inspiration is not, contrasting it with “dynamic” and “mechanical” concepts of inspiration:

Posted in Herman Bavinck, John Frame, Scriptural Authority